This blog post explains the paper “A Dataset Perspective on Offline Reinforcement Learning (presented at CoLLAs 2022). 5-10 min read.

The main contributions of this work are aligned along the question, how algorithms in Offline Reinforcement Learning are influenced by the characteristics of the dataset in finding a good policy. Those are:

- Deriving theoretical measures that capture exploration and exploitation under a policy

- Providing an effective method to characterise datasets through the empirical measures TQ and SACo

- Conducting an extensive empirical evaluation on how dataset characteristics influence popular algorithms in Offline Reinforcement Learning

Introduction

The application of Reinforcement Learning (RL) in real world environments can be expensive or risky due to suboptimal policies during training. This may endanger humans through accidents inflicted by self-driving cars, crashes of production machines when optimising production processes, or high financial losses when applied in trading or pricing. In limiting cases, simulations may alleviate these factors. However, designing robust and high quality simulators is a challenging, time consuming and resource intensive task, and introduces problems related to distributional shift and domain gap between the real world environment and the simulation.

The Offline RL paradigm avoids this problem as interactions with the environment are prohibited during training and training is solely based on pre-collected or logged datasets. Offline RL suffers from domain shifts between the training data distribution and the data distribution under the policy deployed in the actual environment as well as iterative error amplification (Brandfonbrener et al., 2021). Based on model-free off-policy algorithms, in particular DQN (Mnih et al., 2013), algorithmic advances such as policy constraints (Fujimoto et al., 2019a,b; Wang et al., 2020) or regularisation of learned action-values (Kumar et al., 2020) have been proposed among others to cope with this issue.

Datasets in Offline RL

While unified datasets have been released (Gulcehre et al., 2020, Fu et al., 2021) for comparisons of Offline RL algorithms, grounded work on understanding how dataset characteristics influence the performance of algorithms is still lacking (Riedmiller et al., 2021). The composition of the dataset not only limits the possible performance of any algorithm applied to it, its characteristics also have a large influence on the optimal hyperparameters of the algorithm. We found, that it is not a priori clear, how algorithms would perform on a different dataset and that algorithms that excel at one setting might be suboptimal in another. An example for this from our experiments can be seen in the following figure, but similar effects were also reported in the literature (Gulcehre et al., 2021 - Appendix).

While different behaviour can usually be judged and distinguished if displayed through a graphical user interface or visualisation techniques, it is notoriously hard to characterise through single measures.

We therefore implement empirical measures to characterise datasets, which correspond to theoretical measures we base on the explorativeness and exploitativeness of the behavioural policy that sampled the dataset.

Dataset Measures

Measure of Exploitation

We start with a measure of exploitation of the behavioral policy. The expected return of a policy directly reflects how well the policy can exploit the reward function of the environment. The expected return is given by

\[g_\pi = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{t=0}^T \gamma^t R_{t+1} \right].\]Empirically, the expected return is estimated through the average return over the trajectories the dataset consists of. The average return is given by

\[\bar g(\mathcal{D}) = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=0}^B \sum_{t=0}^{T_b} \gamma^t r_{b,t}.\]We normalized the average return with the best and worst behavior observed on a specific environment, which we call trajectory quality (TQ):

\[TQ(\mathcal{D}) := \frac{\bar g(\mathcal{D}) - \bar g(\mathcal{D}_{\text{min}})} {\bar g(\mathcal{D}_{\text{max}}) - \bar g(\mathcal{D}_{\text{min}})}\]In our experimental setup, the minimum return was chosen to be represented by the random policy and the maximum return by an expert policy trained in the usual online RL setting.

Measure of Exploration

Defining a measure for exploration is much harder, as there are many ways to define exploration. Exploration generally serves a purpose, such as acquiring information about the environment dynamics or sampling trajectories that are maximally distant under some distance measure, to name some.

A priori, we do not know the utility of observed transitions to such purposes, which is why we turned to the information theoretic approach of analyzing the Shannon entropy of the transition probabilities under the policy. This transition-entropy is defined as

\[H(p_\pi(s,a,r,s’)) := - \sum_{s,a,r,s’} p_\pi(s,a,r,s’) \log( p_\pi(s,a,r,s’) ).\]The transition-entropy can be rewritten into two terms, where the left one is the occupancy weighted entropy of the transition dynamics and the right term the occupancy-entropy:

\[H(p_\pi(s,a,r,s’)) = \sum_{s,a} \rho_\pi(s,a) \; H(p(r,s’ \mid s,a)) + H(\rho_\pi(s,a))\]The occupancy denotes the probability of being in a certain state-action pair under the policy. For deterministic MDPs, which we conducted our experimental analysis on, the left term vanishes and the transition entropy simplifies to the occupancy-entropy.

\[H(\rho_\pi(s,a)) := - \sum_{s,a} \rho_\pi(s,a) \log( \rho_\pi(s,a) ).\]The following figure provides an intuition about how the occupancy-entropy is related to exploration. The two illustrations on the right show the state-occupancy for a random and a noisy expert policy in a gridworld. Agents start in the upper left corner and have to navigate to the lower right goal tile, but can not pass the walls in between. Intuitively from the plots, one would assume that the random policy did a slightly better job at exploring this environment. We verify this intuition through the distribution of occupancies in the plot to the left. As expected, the random policy attains a higher occupancy entropy than the noisy expert due to its more uniform occupancy distribution. Nevertheless we also see that random exploration is not optimal and more systematic exploration with higher occupancy entropy is possible. This would result in a close to uniform occupancy distribution.

Empirically, we can estimate the occupancy entropy by the naïve entropy estimator \(\hat H(\mathcal{D})\). In practice however, state-action pairs that are present in the dataset more than once do not add extra value to the learning algorithm in a deterministic environment. One could simply choose to sample a specific state-action pair more often for the same effect. Therefore, we based our empirical measure of exploration on the maximum entropy upper bound of the entropy estimator or rather its exponentiated value.

\[e^{\hat H(\mathcal{D})} \leq u_{s,a}(\mathcal{D})\]This upper bound is the number of unique state-action pairs in the dataset. As for the trajectory quality, we normalise the number of unique state-action pairs of a given dataset with those of a reference dataset. We call this measure the state-action coverage (SACo) of the dataset:

\[SACo(\mathcal{D}) := \frac{u_{s,a}(\mathcal{D})}{ u_{s,a}(\mathcal{D}_{\text{ref}})}\]Dataset generation

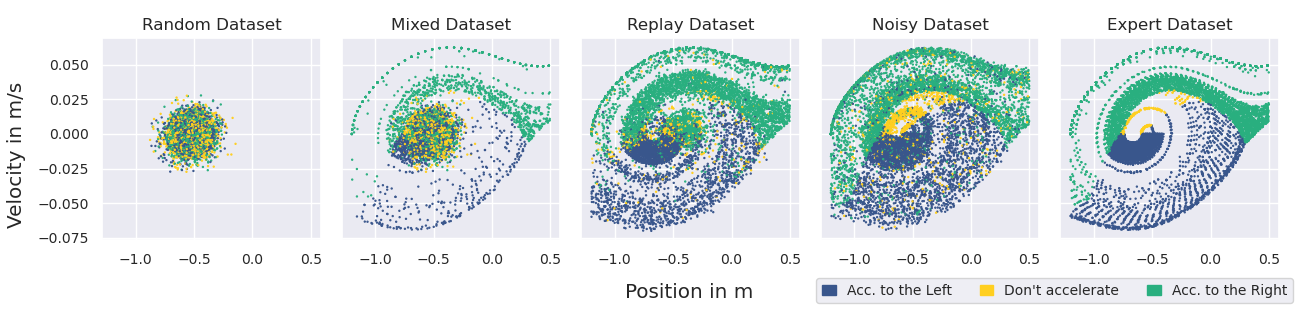

In the offline RL literature, dataset generation is neither harmonised, nor thoroughly investigated yet. We therefore try to systematically cover and extend prior settings from the literature, especially those used in the released collections of datasets (Gulcehre et al., 2020, Fu et al., 2021). Our datasets are generated using the following five settings:

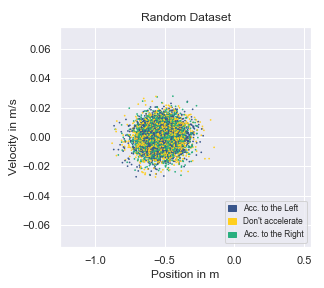

- Random Dataset: A random policy serves as naive baseline for data collection

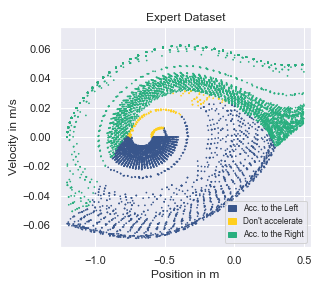

- Expert Dataset: Best policy found during online training used greedy for sampling

- Mixed Dataset: Mixture of random dataset (80%) and expert dataset (20%)

- Noisy Dataset: Best policy found during online training used \(\epsilon\)-greedy for sampling

- Replay Dataset: Collection of all samples generated by online policy during training

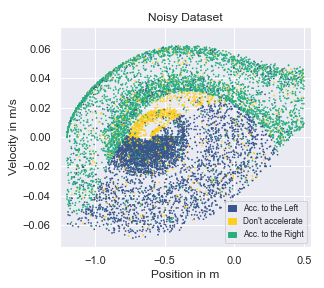

A visualisation of the behaviour contained for different datasets collected in the environment MountainCar-v0 is given below. This environment has a two dimensional state space, making it straightforward to visualise. The colour denotes the issued action given a state.

Using our proposed metrics TQ and SACo, these datasets can be characterised as depicted below.

Experimental results

We conducted our experiments on six environments from three environment suites. These suites range from classic control tasks such as MountainCar, to MiniGrid gridworlds and MinAtar games, which are simplified versions of the popular Atari games. Per environment and dataset generation scheme, five datasets are created with behavioral policies from independent runs.

We train nine different algorithms popular in the Offline RL literature including Behavioral Cloning (BC) (Pomerleau, 1991) and variants of Deep Q-Network (DQN) (Mnih et al., 2013), Quantile-Regression DQN (QRDQN) (Dabney et al., 2017) and Random Ensemble Mixture (REM) (Agarwal et al., 2020). Furthermore, Behavior Value Estimation (BVE) (Gulcehre et al., 2021) and Monte-Carlo Estimation (MCE) are used. Finally, three widely popular Offline RL algorithms that enforce additional constraints on top of DQN, Batch-Constrained Q-learning (BCQ) (Fujimoto et al., 2019b), Conservative Q-learning (CQL) (Kumar et al., 2019) and Critic Regularized Regression (CRR) (Wang et al., 2020) are considered.

In our main experimental results depicted below, we analyse the correlation of the performance of the algorithms enumerated above and the dataset characteristics measured by TQ and SACo. Every point thus denotes one of the datasets created for our experiments and as the same datasets are used for training of each algorithm, those points coincide for all subplots.

We find that BC has a strong correlation with TQ, which is expected as it is cloning the behaviour contained in the dataset. BVE and MCE were found to be very sensitive to the specific environment and dataset setting, favouring those with moderate SACo. Algorithms of the DQN family that search unconstrained for the optimal policy were found to require datasets with high SACo to find a good policy. Finally, algorithms with constraints towards the behavioural policy were found to perform well if datasets exhibit high TQ or SACo or moderate values of TQ and SACo.

Conclusion

We found that popular algorithms in Offline RL are strongly influenced by the characteristics of the dataset, measured by TQ and SACo. Therefore, comparing algorithms using the average performance across different datasets might not be enough for a fair comparison and give a misleading view on the capabilities of each algorithm. Our study thus provides a blueprint to characterise Offline RL datasets and understand their effect on algorithms.

Additional Material

Code on Github: OfflineRL

Paper: A Dataset Perspective on Offline Reinforcement Learning

Prerecorded Conference Talk: CoLLAs Talk

Poster: CoLLAs Poster

Slides: CoLLAs Slides

This blogpost was written by Kajetan Schweighofer with contributions by Andreas Radler and Marius-Constantin Dinu

If there are any questions, feel free to contact us: schweighofer[at]ml.jku.at